Icelandic Horses

Also Known By: Islenzki hesturinn, Icelandic toelter horse, Iceland Tolter

Also Known By: Islenzki hesturinn, Icelandic toelter horse, Iceland Tolter

The Icelandic horse is descended from horses brought to Iceland by settlers over eleven centuries ago. Comparison between the Icelandic horse, at the time of the settlement of Iceland, and ancient Norwegian and German horses show them to have similar bone structure. Some consider it likely that there was a separate species of horse, Ecuus scandianavicus, found in these areas. These horses were later crossed with other European breeds, except in Iceland where it remained relatively pure. Some have said that the Icelandic horse is related to the Shetland but the Icelandic has a genotype which is very different from other European horse populations.

The first Icelandic breed societies were formed in 1904 with the first register being formed in 1923. In the early 1900's the Icelandic horse was used extensively in Iceland for transportation and travel and as a working horse. In the 1940's and 50's its role was coming to an end but it has now been rediscovered in its native country and is recognized as a unique sport and family horse.

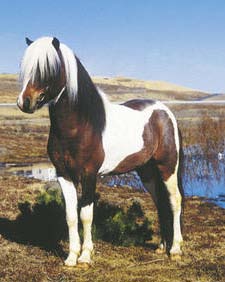

The Icelandic horse is described as a rather small, sturdy and hardy, but not light in build and thus often lacking in elegance. But the strong characteristics of the breed are said to be the versatility in riding performance, lively temperament and strong but workable character. Traditionally the Icelandic horse has been raised free range or in a herd which no doubt is part of the reason for these strong characteristics. The average height is between 13 and 14 hands with an average weight of between 330 and 380 kg. All colors are found except appaloosa marking, with the most common being chestnut. All white markings are acceptable and there are pinto in all of the base colors. The horses have long, thick manes and tails and the winter coat is double. The appearance of the Icelandic horse in countries outside of Iceland has changed somewhat due to upgrading programs used during the 1950's.

Although traditionally the Icelandic horse was raised free range this is no longer the case. During the 1900's the breeding and rearing of Icelandic horses has changed and is now very similar to horse breeding found throughout Europe and North America.

In Iceland, although breeding of riding horses is the main objective, meat production is going on as well, even though no special consideration has been given to that aspect as far as breeding is concerned. The meat was once a very valuable commodity but has declined somewhat due to increased competition and decreased popularity. Much of the meat is now exported to Japan.

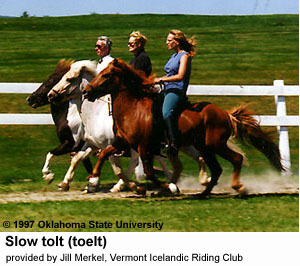

In addition to the standard walk, trot and canter, the Icelandic horse has tolt, a “running walk” similar to the gait found in the American Saddlebred, Paso Fino and Tennessee Walker. Some are also bred for a special "flying pace" or skold, which is a very fast lateral gait used for racing short distances. Some horses can reach almost 30 miles an hour using this pace.

Diseases are almost unknown among Icelandic horses. Protection of the horses is assured by the strict regulations of the Icelandic government. No horse which has been taken out of Iceland can come back into the country. Also only new, unused horse equipment may be taken to Iceland. This is to prevent an outbreak of disease which could decimate the population of Icelandic horses.

Because Iceland has no predators, but instead is a country with tremendous environmental danger, such as quicksand, rock slides, rivers with changing currents, the ability to assess a situation rather than the instinct to flee, have been central in the survival of the horse. Therefore, these horses lack the “spookiness” that characterizes most horses. Due perhaps to their lack of fear of living things, they seek strong attachments to people and are quite nurturing and affectionate.

The breed standard for Icelandic horses is uniform throughout the world, as are registration rules, rules of breeding competitions and rules of performance competitions. All such activities are strictly regulated by the international association for Icelandic horses. Training by any artificial methods is strictly forbidden.

References

Hendricks, Bonnie L., International Encyclopedia of Horse Breeds, Univ of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Hugason, K. 1994, Breeding of Icelandic toelter horses: an overview. Livestock Production Science 40, 21-29. The Agricultural Society of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland.

United Icelandic Horse Congress, 38 Park St., Montclair, NJ 07042. Phone: (201) 783-3429

Kentucky Horse Park, 4089 Iron Works Pike, Lexington, KY 40511

United States Icelandic Horse Congress, 6800 East 99th Avenue, Anchorage, Alaska 99507 (907) 346-2223 (telephone & fax)

Email: icecong@aol.com

Icelandic Horses Gallery Take a closer look at the Icelandic breed.