Old Norwegian Sheep

Also Known By: Gammelnorsk, Utegangarsau, Vildsau

Also Known By: Gammelnorsk, Utegangarsau, Vildsau

The Old Norwegian is of the old Northern short-tailed breed. It is found in Selbjorn, Austevoll and Horda (Sunnhordland) in western Norway. Adult males weigh on average 43 kg and females 32 kg. This breed is thought to be the origin of the Icelandic, Faeroes and Spælsau breeds.

One of the most spectacular animals on the Western coast of Norway, also present on the island of Froya, is the old Norwegian breed of sheep which are called "gammel norsk spælsau" or in English translated to: Old Norwegian Sheep, (ovis brachyura borealis). This breed represents one of the most primitive kinds of domestic sheep still present in Europe, probably only the feral Soay Sheep at St. Kilda are more primitive. How is it possible that a relic population of such an old breed of sheep should have survived on the Norwegian West coast?

- First it was represented by the rest of the old Atlantic type of agricultural tradition, still surviving on the islands of the Western coast of Norway, like many other of the remote islands in Northern Europe.

- The inaccessibility of the region itself prevented import of other breeds.

- The people living on the coast themselves, valued the animals very much and used the unique mutton and the wool as well for production of high quality craft products.

- But most of all the sheep itself because of their ability to survive in extreme winter conditions.

- The Old Norwegian Sheep is better adjusted to the climate and the poor vegetation on the coast than many wild animals like deer and roe-deer.

- The animals graze the whole year and even in the winter they find food outside and have a minimum of artificial shelter and feeding.

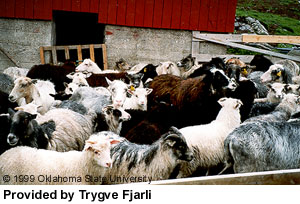

The Old Norwegian Sheep is the small primitive type of sheep which inhabited Norway and the rest of Scandinavia as well, including Iceland and Faeroes, and was probably present on the Western islands too. Remains of similar type of sheep discovered near Bergen, are dated to be 3000 years old. Today the largest number of the sheep is found in the region around Bergen and along the coastline and on the islands outside Trondheim. The population of Old Norwegian Sheep numbers around 10,000 animals. This number is in great contrast to the situation around 1955, when the breed had almost disappeared. Other breeds and new agricultural methods as well as misunderstanding from the society for the prevention of cruelty to animals led by high society ladies in Bergen, almost set the rest of the breed on the road to destruction because of what they believed to be mismanagement of domestic animals.

The Old Norwegian Sheep is the small primitive type of sheep which inhabited Norway and the rest of Scandinavia as well, including Iceland and Faeroes, and was probably present on the Western islands too. Remains of similar type of sheep discovered near Bergen, are dated to be 3000 years old. Today the largest number of the sheep is found in the region around Bergen and along the coastline and on the islands outside Trondheim. The population of Old Norwegian Sheep numbers around 10,000 animals. This number is in great contrast to the situation around 1955, when the breed had almost disappeared. Other breeds and new agricultural methods as well as misunderstanding from the society for the prevention of cruelty to animals led by high society ladies in Bergen, almost set the rest of the breed on the road to destruction because of what they believed to be mismanagement of domestic animals.

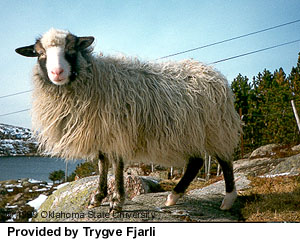

The sheep are small framed, with good legs and a fleece varying in color from almost white to grayish, dark brown, badger face, muflon pattern and black. Normally the sheep shed their fleece naturally in early July. All the males of this breed are horned and approximately 10 % of the ewes are horned and the rest are polled. The horns on the females are short and goatish. The males have normally well-developed mouflonlike horns.

The fleece is remarkably fine and in contrast to the mouflon, the inner fleece is highly developed. The outer coat has long fibers, up to 30 cm around the neck on the males. The wool is highly valued for making high quality craft products like hand knitting yarns and for felt-making and many other purposes.

The fleece is remarkably fine and in contrast to the mouflon, the inner fleece is highly developed. The outer coat has long fibers, up to 30 cm around the neck on the males. The wool is highly valued for making high quality craft products like hand knitting yarns and for felt-making and many other purposes.

In contrast to the Soay Sheep on St. Kilda who lack the flocking instinct, the Old Norwegian Sheep has developed a very strong flocking instinct. Normally a flock of less than 5 to 7 animals will not be able to establish the social structure needed in a flock. Because of this very strong flock instinct the breed is now tested for use in grazing areas with predators like bear, wolf, lynx and wolverine.

This breed of sheep has a unique pattern of flight (escaping an enemy). This also makes it suitable for use in grazing areas with predators. This flight behavior makes it difficult to handle them with normally trained sheep dogs. The dog will only come back with a few animals because the weak ones escape the flock and hide till the animals in best condition are left with the dog. The same flight pattern will occur on the grazing land where a small group of the best animals will end with the predator and exhaust it. There is normally little, if any loss at all of Old Norwegian Sheep to predators compared to other breeds in the same area. More research is needed to prove it.

The maternal instinct of the Old Norwegian Sheep is very strong. Their behavior is similar to that of the American Bighorn sheep. The mother leaves the flock to give birth from 12 hours to 3 days before the lamb is born and stays alone with the lamb for another 3 to 6 days before returning to the flock. The lambs are strongly defended against enemies if necessary. At the age of 14 days the lambs are developed enough to follow their mothers and to join play-groups of lambs as well. By this time the lambs begin to graze too.

Keeping Old Norwegian Sheep was rather unprofitable until the owners organized themselves in "Norsk Villsaulag". This is an organization working for distribution and trading with meat and other products from the sheep and they are able to pay the members a good price. Unlike the meat from other breeds the Old Norwegian Sheep has the fat located to the kidney region and around the gut. Since the taste is located to the fat, and the meat from the Old Norwegian Sheep has very little fat in the meat, the taste is more reminiscent of roe-deer and reindeer than mutton. The production is also ecological since the animals usually graze outside on land with no surplus of fertilizer all the year through. The animals normally get very little surplus feeding, if any feeding at all. The veterinary directions of Norway instruct the farmers to feed in periods with hard weather. At the moment, the market is just insatiable for the meat. Today just a part of the restaurant market is supplied. A group is working with the market for wool and other products from the sheep.

Keeping Old Norwegian Sheep was rather unprofitable until the owners organized themselves in "Norsk Villsaulag". This is an organization working for distribution and trading with meat and other products from the sheep and they are able to pay the members a good price. Unlike the meat from other breeds the Old Norwegian Sheep has the fat located to the kidney region and around the gut. Since the taste is located to the fat, and the meat from the Old Norwegian Sheep has very little fat in the meat, the taste is more reminiscent of roe-deer and reindeer than mutton. The production is also ecological since the animals usually graze outside on land with no surplus of fertilizer all the year through. The animals normally get very little surplus feeding, if any feeding at all. The veterinary directions of Norway instruct the farmers to feed in periods with hard weather. At the moment, the market is just insatiable for the meat. Today just a part of the restaurant market is supplied. A group is working with the market for wool and other products from the sheep.

The careful grazing habit of the Old Norwegian Sheep makes it suitable to keep vegetation away from monuments and ruins and cultural heritage formed by agriculture and other cultivation. Heather, (calluna-heath) is important for winter feeding and the heath needs to be cultivated and the best maintenance of the heath is careful grazing with the Old Norwegian Sheep.

References

Trygve Fjarli, Norway

Mason, I.L. 1996. A World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types and Varieties. Fourth Edition. C.A.B International. 273 pp.